I stepped off the plane in Oslo, Norway excited to attend the Oslo Freedom Forum, a gathering of the world’s most notable human rights activists, journalists, policymakers, technologists, and artists who share the goal of making the world a more democratic and peaceful place. After spending the semester abroad in Jordan and traveling to Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Israel, and Turkey, I was ready to engage in a community of activists working to promote human rights in that region and across the world.

However, wandering around the city of Oslo before the forum began, I couldn’t shake a nagging question: “What am I doing here?” The conflicts I want to work on, the languages I want to learn, and the people whose lives are touched by those conflicts were all back in the region I had just come from. What was I doing in this idyllic European city that felt so far removed from where I’d spent the past four months?

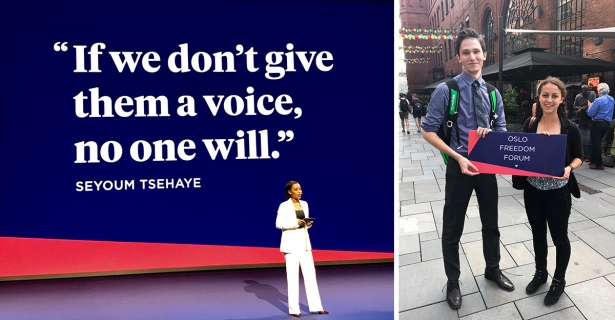

The Oslo Freedom Forum began with a press conference that Thor Halvorssen, president of the Human Rights Foundation, opened with the words, “From this very safe place in Oslo… we can help the world.” He then turned the conversation over to the row of activists beside him who came from North Korea, Venezuela, Egypt, Russia, Nicaragua and other countries. To me, their stories reflected true activism. They were practicing many of the 198 methods of nonviolent action described by the Albert Einstein Institution, and sometimes using their own new methods.

Over the next three days, though, Halvorssen’s opening remarks sunk in. Listening to speakers from across the world, I realized that we were fortunate to be in such a safe place. We were in Oslo because Norway guarantees anyone within its borders freedom of speech, press, and assembly. Holding the forum in the countries I visited last semester is a political impossibility. In many countries across the world, activists face censorship, denial of entry, imprisonment, torture, or even death for the work they do.

Wael Ghonim, internet activist and symbolic leader of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, was imprisoned and tortured for calling on people to protest police brutality. He now lives in exile. Mai Khoi, a popular Vietnamese singer and activist, faces censorship and government pressure to stop speaking out for LGBT and women’s rights. In Oslo, however, it is possible for them to share their stories, discuss strategies with fellow activists, and connect with journalists, donors, and technical experts who can support their causes.

Listening to and speaking with the forum participants, I realized the many freedoms I take for granted in the U.S. as well as some I had never previously considered. The freedom to research and analyze case studies about successful nonviolent resistance on an uncensored Internet is a privilege. The freedom to publish this research and distribute it globally is a privilege. The freedom to connect with activists across the world and share resources on nonviolent methods of resistance is a privilege. By working with the Albert Einstein Institution this summer as an Oslo Scholar, I hope to take advantage of these privileges to play a role in supporting nonviolent activism and democratic practices across the world.